Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of the largest ancient city ever found in Egypt. (Photo by Khaled Desouki)

Egyptian archaeologists have discovered what is believed to be the largest city of the Egyptian empire and the most important archaeological discovery since King Tut’s tomb nearly a century ago.

Lost under desert sands for three millennia, the ruins of the “Lost Golden City” date back over 3,400 years to the reign of Amenhotep III, the ninth king of the 18th dynasty, who ruled ancient Egypt during a golden period of peace and prosperity.

“Many foreign missions searched for this city and never found it,” Dr. Zahi Hawass, the former Egyptian Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, said in a statement. The famed archaeologist was leading an Egyptian team in search of Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple when they made the discovery last September. The excavation area is located near Luxor, between Rameses III’s temple at Medinet Habu and Amenhotep III’s temple at Memnon.

The discovery is said to be the most important archaeological find since the tomb of King Tut. (Photo by Stringer/Anadolu Agency)

“To the team’s great surprise, formations of mud bricks began to appear in all directions,” said Dr. Hawass. “What they unearthed was the site of a large city in a good condition of preservation, with almost complete walls, and with rooms filled with tools of daily life. The archaeological layers have laid untouched for thousands of years, left by the ancient residents as if it were yesterday.”

“It’s very much a snapshot in time—an Egyptian version of Pompeii,” Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, told National geographic . “I don’t think you can oversell it. It is mindblowing.”

Dr. Hawass’s team was able to date the settlement from hieroglyphic inscriptions found on clay caps of wine vessels and mud bricks bearing seals of King Amenhotep III’s cartouche.

An excavation worker cleans a pottery vessel unearthed from the archeological site of the “Lost Golden City.” (Photo by Ahmed Gomaa)

In the first seven months of excavations, Dr. Hawass’s team has unearthed several neighborhoods, including a bakery. Among the findings are jewelry, pottery vessels, scarab beetle amulets, and the tools of spinning, weaving and other daily activities, giving archaeologists a rare glimpse into ancient Egyptian life.

Dr. Zahi Hawass, Egyptian archaeologist, examines pottery vessels found in the “Lost Golden City.” (Photo by Mahmoud Khaled)

The city was the largest administrative and industrial settlement during the 18th dynasty, when ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. Dr. Hawass said that the city extends west, “all the way to the famous Deir el-Medina,” the village that was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

Zigzag walls were used in ancient Egyptian architecture, mainly toward the end of the 18th Dynasty. (Photo by Mahmoud Khaled)

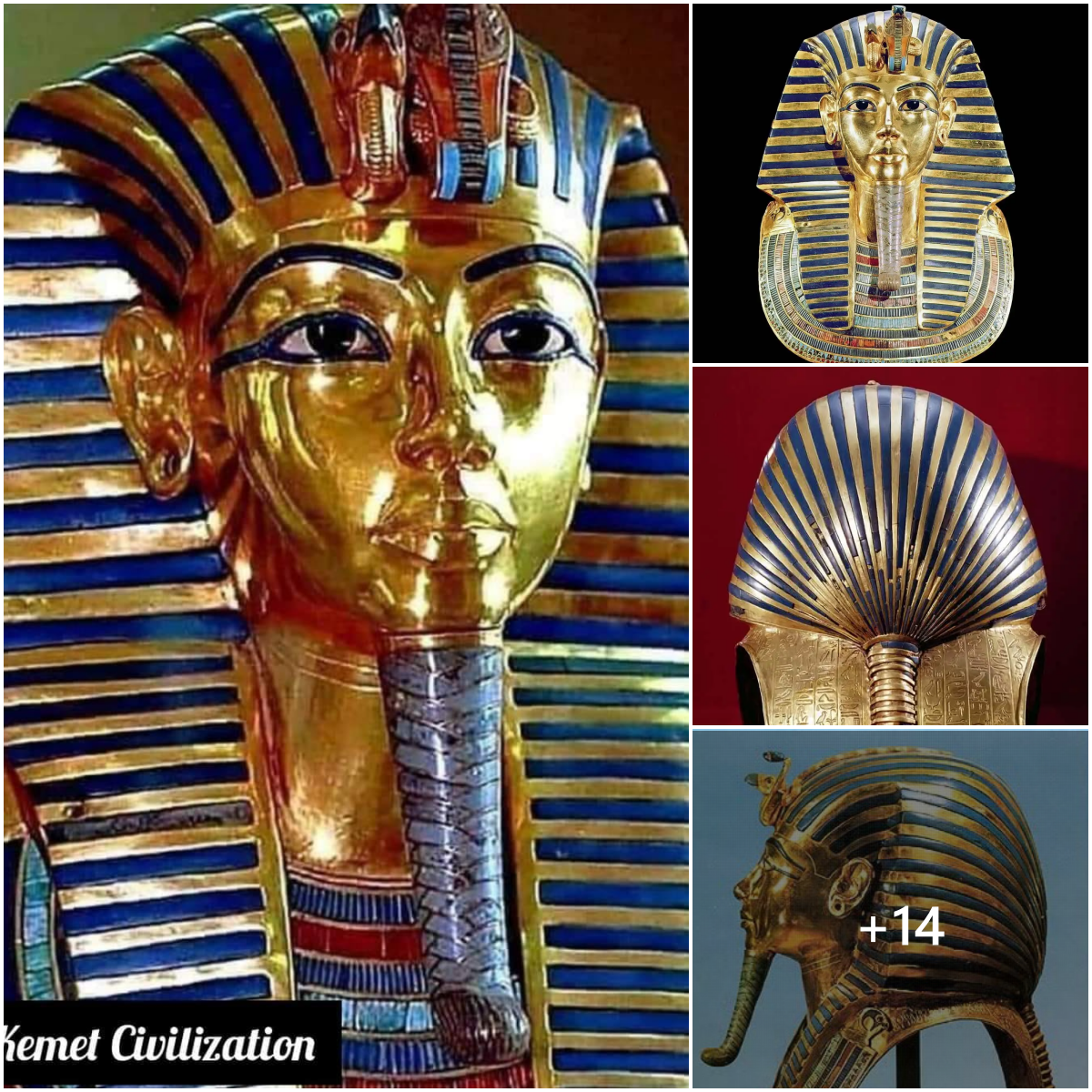

GETTY IMAGES

An area with well-arranged units is “fenced in by a zigzag wall, with only one access point leading to internal corridors and residential areas,” said Dr. Hawass. “The single entrance makes us think it was some sort of security, with the ability to control entry and exit to enclosed areas.”

A skeleton at the archaeological site of the 3,000-year-old Lost Golden City. (Photo by Khaled Desouki)

Some of the more surprising discoveries include the skeleton of a cow or bull found inside one of the rooms. “And even more remarkable burial of a person found with arms outstretched to his side, and remains of a rope wrapped around his knees,” said Dr. Hawass. “The location and position of this skeleton are rather odd, and more investigations are in progress.”

Scores of vessels and tools have been discovered in the Lost Golden City uncovered near Luxor, home of the legendary Valley of the Kings. (Photo by Khaled Desouki)

“The discovery of this lost city is the second most important archeological discovery after the tomb of Tutankhamun,” said Betsy Brian, professor of Egyptology at John Hopkins University. “The discovery of the Lost City not only will give us a rare glimpse into the life of the Ancient Egyptians at the time where the Empire was at his wealthiest but will help us shed light on one of history’s greatest mysteries: why did Akhenaten and Nefertiti decide to move to Amarna?”

Some of Dr. Hawass’s discoveries are already providing valuable clues. For instance, a pottery vessel inscribed “Year 37” confirms that the city was active during King Amenhotep III’s co-regency with his son Akhenaten.

“As history goes, one year after this pot was made, the city was abandoned and the capital relocated to Amarna. But was it? And why? And was the city repopulated again when Tutankhamun returned to Thebes?” asked Hawass. “Only further excavations of the area will reveal what truly happened 3,500 years ago.”