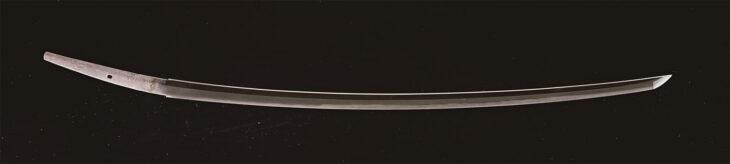

Blade for a Long Sword (Tachi), Named “Meibutsu Mikazuki Munechika” by MunechikaHeian period, 10th–12th centuryPhoto: Courtesy of Tokyo National Museum

Sato Hirosuke, General Manager of the Registration Office, Tokyo National Museum

Sato Hirosuke

The 150th Anniversary Special Exhibition “Tokyo National Museum: Its History and National Treasures” held at the Tokyo National Museum (TNM) from October 18 to December 18, 2022, put 89 national treasures from the museum’s collection on display (objects on display change during the exhibition period). Nineteen national treasure swords were displayed throughout the entire exhibition period, the first time that they had been shown together. I myself had never seen all of them side by side, so this was a rare opportunity.

As of 2022, there are 122 swords throughout Japan designated as national treasures. It was possible to see almost 20% of them in this exhibition.

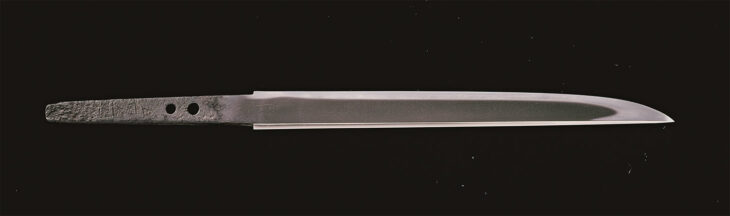

Among the swords were those counted among the “Tenka-Goken” (the greatest five swords of Japan), namely the Blade for a Long Sword (Tachi), Named “Meibutsu Mikazuki Munechika” and the Blade for a Long Sword (Tachi), Named “Meijibursu Dojigiri Yasutsuna.” Their respective makers, Munechika of Kyoto and Yasutsuna of Hoki Province (now Tottori Prefecture), were both master sword smiths of the Heian period (794–1185). Later I will compare the differences in style between these and other swords.

Blade for a Long Sword (Tachi), Named “Meijibursu Dojigiri Yasutsuna” by MunechikaHeian period, 10th–12th centuryPhoto: Courtesy of Tokyo National Museum

Additionally, visitors were able to see superb swords long considered “meibutsu” (famous), such as Blade for a Long Sword (Tachi), Named “Meibutsu Okanehira” by Kanehira of Bizen Province (currently Okayama Prefecture) and the Blade for a Dagger (Tantō), Named “Meibutsu Atsushi Tōshirō” by Yoshimitsu. Since so many masterpieces were displayed, a dedicated “National Treasure Sword Room” was prepared especially for the swords. The sight of these top-class swords lined up in the same space was spectacular. The display cases were of the latest kind and completely transparent so as to create an environment where visitors could enjoy all the details. The room was darkened to remove any distractions from the field of view, while the lighting was adjusted to highlight the shine of the swords.

Blade for a Long Sword (Tachi), Named “Meibutsu Okanehira” by Kanehira of Bizen ProvinceHeian period, 12th centuryPhoto: Courtesy of Tokyo National Museum

Blade for a Dagger (Tantō), Named “Meibutsu Atsushi Tōshirō” by YoshimitsuKamakura period, 13th centuryPhoto: Courtesy of Tokyo National Museum

Swords are on general display as part of the museum’s permanent exhibition, but there usually are only one or two national treasures on show at any one time. Therefore, it takes four or five years to rotate all of the national treasures, so a simultaneous display of this scale was rare.

The swords are not rotated to put on airs, but rather as a way for the museum to fulfill its role as a protector and conveyor of cultural properties. Many of Japan’s cultural properties are made entirely of fragile materials, so exhibitions need to be restricted in some ways. If an object is left exposed for too long, it may deteriorate and the thing itself will be lost.

Balancing conservation and exhibition is the mission of museums. One of the answers that those who went before us came up with as a way to properly fulfill this role is to limit exhibition periods. National treasures and important cultural properties can only be shown to the public for a total of 60 days per year.

The same brilliance as in the Heian period

This may seem a little strange. In short, it is natural to be careful about damage to paintings drawn on Japanese paper or dyed silk textiles, but swords will not break easily. It is true that Japanese swords are made of iron, so they are indeed strong. However, it is also true that they rust very easily.

If you leave swords outside in a country like Japan with high humidity and big fluctuations in temperature, they are sure to rust. Although they are kept in a case with thorough humidity and temperature control, the risk of rust cannot be completely eliminated as long as they are exposed to the air.

As such, the guideline for rotating sword exhibits is two to three months, and when not on display, the surface of the swords is oiled to create a film that blocks out air and they are stored in plain-wood scabbards in a storage room with thorough humidity and temperature control. This imitates traditional storage methods.

Moreover, decorations such as scabbards meant to contain swords require even more care. Many of them were damaged in battle or have decayed because they are made of wood. However, at this exhibition, visitors could see scabbards with wonderful decorations, such as Ceremonial Sword Mounting (Kazari Tachi) with mother-of-pearl inlay decoration and gold fittings on a nashiji lacquer surface, and Chain-Fitted Sword Mounting (Hyōgo Gusari no Tachi) with Flocks of Birds, Named “Uesugi Tachi” by the Ichimonji school. It is essential that these too are handled with the utmost care to preserve their original appearance.

Ceremonial Sword Mounting (Kazari Tachi) with mother-of-pearl inlay decoration and gold fittings on a nashiji lacquer surfaceHeian period, 12th centuryPhoto: Courtesy of Tokyo National Museum

Chain-Fitted Sword Mounting (Hyōgo Gusari no Tachi) with Flocks of Birds, Named “Uesugi Tachi” by the Ichimonji schoolKamakura period, 13th centuryPhoto: Courtesy of Tokyo National Museum

This attention to care has continued uninterrupted over time, and all existing swords have been treated like this for hundreds of years. Thanks to the care of countless people, the swords have the same brilliance as when they were first made.

For example, the aforementioned “Mikazuki Munechika” is a sword made during the Heian period, but it has maintained its brilliance. This is because people have been taking care of it for about 800 to 900 years, handing it down with great care.

People in every time period must have had exactly the same feelings about this sword as we do, “Oh, it’s wonderful. It’s beautiful.” If someone along the line had thought “It’s no big deal” or “It’s damaged so I won’t care for it anymore,” then the sword would surely have disappeared at that point.

The fact that “Mikazuki Munechika” is on public display is proof that the spirit of appreciating something’s beauty and preciousness has been passed down for a long time. I feel that the inheritance of cultural properties is a very human activity.

What to look for in a sword?

So, how should we appreciate the rare swords that have been handed down to the present day? We often hear people say, “It’s hard to know what to look for,” or “Every sword looks the same.”

In order to enjoy the 19 swords that are national treasures, here are three basic points that can help you appreciate the differences.

Basically, there is the sugata (sword shape), the jigane (the sword’s ground metal), and the hamon (the blade patterns) that is quenched on the cutting edge. These three main features give rise to a sword’s personality and unique characteristics.

First of all, the sugata, which refers to the overall shape of the sword blade, such as its warping and width, and its impression.

All sword blades are long and thin, but if you look at them with an open mind, you can feel big differences in directionality, with some having a gorgeous and strong appearance while others appear neat and elegant.

These differences often reflect the era and region of their making. The sword blade of the aforementioned “Mikazuki Munechika” is slender and thin, and has a strong warp closer to the handle. It extends from the warped end and gradually becomes thinner, finally tapering to a fairly small tip.

The game Touken ranbu (Wild Dance of Swords) that is popular nowadays also features “Mikazuki Munechika” as a character. In the game, he is portrayed as a slender man like a Heian noble, an image that is evoked exactly by the actual sword blade as well.

The sleek and graceful figure basically represents the aesthetic sense of the capital and especially the court nobles. The curvaceous and neat appearance of court nobles is fully expressed in “Mikazuki Munechika.” You can read this just by looking at its sugata, its shape.

Model change according to fighting style

If systematized, the sugata shape of a sword accurately represents the era in which a sword was made. Just as automobiles are remodeled, swords have also changed with the times.

These changes are basically linked to the way warfare was conducted. Swords are weapons, so this is only natural.

In Japan, in ancient times from the Heian period to the Kamakura period (1185–1333) and the Nanbokucho (North and South court) period (1337–1392), fighting on horseback was most common. Enemies and allies alike fought on horseback. The weapons that a warrior carried to such a battle were more effective the longer their reach, so swords from ancient times are fundamentally longer.

When the style of warfare changed to group warfare on foot after the middle of the Muromachi period (1336–1575), shorter sword blades, which were easier to handle, were preferred to long ones. Along with this, the direction of the blade sheathed from the waist also changed.

Until that time, they were called “tachi,” which was hung with the blade down, but after the advent of fighting on foot, the blade was pointed up and sheathed at the waist. These were called “katana.” So, depending on the direction of the blade when sheathed, there are two main types of sword: tachi and katana.

Further back in time there are also straight swords without warp. Many of the national treasure swords are very old, mostly ranging from straight swords to those from the Heian, Kamakura, and Nanbokucho periods.

The second feature to look for with swords is the jigane (ground metal).

Japanese swords are made through a repeated process of striking a lump of steel, stretching it, and striking it again. This is a process to increase strength and purity, wherein the steel is folded in multiple layers, creating many thin layers. By sharpening this, the layers emerge as a ground pattern. This is the jigane.

However, the ground pattern of the jigane is so faint that it is difficult to tell at first glance since the flat surface is reflective like a mirror. However, if you look at the blade from different angles, you can see the jigane like wood grain.

The jigane of a blade made by a skillful sword smith looks like glittering marbled meat with fine streaks of fat. By contrast, if a bad sword smith makes a sword, it will feel rough and as though it has cavities. In short, differences in fineness of texture are reflected in the jigane. Such differences are evident between sword smiths and schools.

Patterns differ between Kamakura and Kyoto

There are provincial characteristics tied to the place of manufacture, with some regions prominently bringing out the ground pattern of the jigane and others aiming for uniform and precise jigane by reining it in as much as possible.

The most prominent jigane comes from Soshu Sagami Province (present-day Kanagawa Prefecture) and a school of “Soshu den” (Swords from Sagami Province), represented by master sword smith Masamune. The reason why these masters emerged is because Soshu den was a school established in Kamakura.

Needless to say, Kamakura is the birthplace of the first samurai government in Japan. Sword smiths, working hard to make swords there, aimed for powerful swords that matched the spirit of the samurai. As a manifestation of this style, many were made with highly prominent jigane.

On the other hand, an example of swords without prominent jigane are those from the capital Kyoto. The capital’s value system did not accept rough things but esteemed elegance, mellowness and beauty. This was embodied by Yamashiro family of sword smiths in Kyoto. This style was best exemplified by the aforementioned Atsushi Toshiro, whose “Yoshimitsu” is a masterpiece and a fine example of the beautiful jigane created by the Yamashiro sword smiths. It is a tanto (short sword), also known as kaito, which was always worn by samurai. It was also used when the katana broke, when stabbing an opponent, or when committing harakiri ritual suicide. A defensive sword and a last resort, the tanto also has examples that are very well made.

The third and final feature to look for on a sword is the hamon (blade pattern). This refers to the white streaks and wave patterns that appear on the blade’s cutting edge, so it is relatively easy to understand.

Hamon manifests itself through a process called quenching.

In making a sword, there is a process of heating and rapid cooling at the end. In this process, only the blade part acquires increased hardness and sharpness. In this process, the sword blade is protected by applying blade clay, and it is this that creates the hamon. There is no way to completely control what kind of pattern appears, so the pattern is random to some extent. As such, depending on the sword, some hamon are straight and others uneven.

Hamon also have a provincial character, with the Yamashiro sword smiths in the capital pursuing straight hamon. The Yamashiro long pursued a straight, neat, bright, and clear aesthetic.

By contrast, the sword smiths of Okayama in Bizen Province sought to produce glamorous hamon. They created gorgeous hamon that were popular with everyone from court nobles to samurai, and beloved by a wide range of people.

Jigane and hamon are clearly visible because the surface of a sword is polished like a mirror. In addition to being cared for thoroughly and having rust kept at bay, superb swords have not lost their brilliance because they were originally polished with first-class togi (polishing) techniques.

Togi is also unique to Japanese sword culture. Japanese swords are blades, and if the manufacturer were only concerned about the swords’ function of cutting, it would be enough merely to sharpen the cutting edge. But for a Japanese sword smith, that would not suffice. Since ancient times, aesthetic aspects have been equally emphasized. The whole sword is burnished, so it is not complete until both jigane and hamon are brilliantly brought to the surface.

How sharp are they really?

The key points for appreciating a sword so far mentioned have to do with their appearance, but what of their actual practical utility. For example, one wonders, how sharp Japanese swords really are.

I have personally never used one, but it is said that they are tremendously sharp. This is because, to begin with, Japanese swords have been made for a sole function: cutting.

Japanese swords were made ultimately to be used, and as such emphasis was placed not only on their sharpness but also their durability. There is a saying, “It does not break, does not bend, and cuts well,” so it was considered important that the swords did bend or break in addition to being able to cut well, meaning that they were created with sufficient strength in mind. Certainly, on the battlefield, the swords would have been useless if they bent or broke easily.

Approaches that combine sharpness and robustness are included in the way Japanese swords are made and structured. Japanese swords crystallize weapon functionality, and at the same time it is possible to discern in them a value particular to Japanese culture, “beauty of use.”

From this point of view, Japanese swords are typical of Japanese culture and may even be said to be the epitome of Japanese beauty.

The TNM exhibition featured all 89 national treasures from the museum’s collection. Of these, 19 are swords, which is a high percentage of total national treasures. Nationwide, there are 122 national treasure swords, accounting for about half of all national treasure crafts.

The reason why there are so many national treasure swords is primarily because swords are cultural properties emblematic of the Japanese aesthetic.

However, a slightly more realistic reason is that swords have been valued for a long time.

Heian period paintings depict aristocrats gazing intently at a sword blade. It is proof that value was attached to swords not only as excellent weapons but also as objects of beauty.

“Catalogs” of superb swords have existed from the Heian period to today. Such catalogs would include the names of the makers, so information such as “There is a sword smith in this area whose work is excellent” was widely circulated.

It is said that Emperor Gotoba (1180–1239) in the Kamakura period invited a sword smith to the court to work for him, so the connection between court nobles and sword smiths reaches far back.

In the Edo period (1603–1867), a book called Kyoho Meibutsucho (book of special swords of Kyoho [1716–1736]) was compiled during the reign of the eighth Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684–1751). This was, so to speak, the definitive edition of a superb swords “encyclopedia.” The historical facts listed there remain extremely effective for the appraisal and evaluation of swords.

In this way, evaluation criteria and research on Japanese swords have been growing since the Heian period, firmly establishing the evaluation of each sword.

This background might explain why the selection of national treasures and important cultural properties has been fairly smooth under the Cultural Properties Protection Law. It is difficult to select objects whose evaluation is undetermined, but if it is possible to say, “It has been valued since the Heian period, with literary sources to back it up,” then a candidate object can be selected with confidence. As such, from the early days when the national treasures designation system was first established, suitable Japanese swords have been made national treasures. Conversely, no swords have been designated as national treasures in the last 30 years or so.

Follow the sword girls!

In recent years, the popularity of Touken ranbu has sparked a sword boom among young people. As someone working with swords, I’m glad that people are taking an interest. Whether it’s a game or anime, I don’t mind it as long as more people take a look at the swords.

Rather, I am grateful that swords are considered a form of Japanese traditional culture worthy of reappraisal. This is because swords have often been talked about in terms of weapons, murder blades, and so forth. They were of course made as weapons to slash people, but that does not mean they should be dismissed as terrible or scandalous.

Why have so many Japanese swords been passed down through the ages, several becoming national treasures and important cultural properties to be exhibited at museums? It is because they are widely regarded as a works of art that go beyond being mere weapons. It is important to pay attention to this value as well.

With Japan’s defeat in World War II, Japanese swords were on the verge of disappearing. There was a tendency to confiscate and dispose of them as weapons, but people working with swords at the time made desperate appeals.

“They are not just weapons but part of the culture and soul of Japan, given form as works of art.”

The GHQ acknowledged this claim, and today we can enjoy and appreciate the beauty of Japanese swords. This was the insight of our forebears.

Why I got hooked on swords

Due to the popularity of Touken ranbu right now, young people of both genders visited the swords corner at the TNM exhibition, some of them seemingly more knowledgeable than me as an expert as they went around looking at the swords from across the country.

Personally, I haven’t loved swords since I was a child, but I got hooked on the world of swords through various encounters and chance meetings.

Aspiring to become a museum curator, I got a job at the Okayama Prefectural Museum, was told “Starting today, you’re in charge of these swords,” and was assigned to the famous national treasure, Tachi Mumei-Ichimonji (Yamatorige). It is said that it got the nickname “Yamatorige” because the great waves of its hamon resemble the feathers of a mountain bird.

Through this superb sword, I not only learned techniques for working with swords but also what mindset to have when facing the essence of the swords, among many other things.

Crafts of such excellence that they are designated as national treasures undoubtedly contain an extraordinary amount of information and energy.

When I think about it, the best part of art appreciation is coming face to face with the real thing. This time, in particular, you will be able to get an experience of encountering swords up close, and by comparing them side by side, you will be able to understand their differences and highlights intuitively.

It would be a great pleasure for me if you could get acquainted with these various swords.

Note: This article was originally published by Bungeishunju in November 2022 during the exhibition, The 150th Anniversary Special Exhibition “Tokyo National Museum: Its History and National Treasures.”

Translated from “Kokuho ‘Token’ wo mederu (Admiring national treasure “swords”),” Bungeishunju, December 2022, pp. 320–327. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju, Ltd.) [January 2023].